Interlude

So how did I get there, to Terapia Intensiva in Policlinico Umberto I?

Trastevere. 29 December 2018.

On our first morning in Rome, while most of the family were still in bed, I took the short walk from our Airbnb to the Basilica of Santa Maria in Trastevere. I’ d last seen it on my honeymoon in 1992. I sat on a pew and – since you never know when it might come in – made a phone recording of the ambience of the church, with its other visitors and a Kyrie piping through speakers. In the portico, I looked, without understanding, at Latin and Greek on bits of stone, stuck to the wall like a ransom note from the past.

Not that I needed one. Over the next few days we paid our dues to the city’s imperial and ecclesiastical history. Back then, I had no thoughts about joining them in the past tense. We went to the Pantheon. We passed a colonnade just as a light show projected images of Emperor Hadrian and fire and ivy and described how these pillars ceased to be part of the Temple of Hadrian and became the facade of the Rome Chamber of Commerce. Santa Maria Maggiore – where Pope Francis was buried in 2025 – was the first of the churches. We ended up in St. Peter’s Square more than once. Winter sun or evening spotlights contrasted sharply with dark archways and even darker skies. Between times, we simply walked, ate our favourite foods and spoke to street cats. Christmas had been messy and fragmented but now this was our time together as a family: a refresh before returning to work or study.

On Facebook, on the last day of 2018, I posted this:

Hmm.

Later that night – doing as Romans do – we climbed up Janiculum Hill. From the top we would see the New Year fireworks explode all over the city. We came to some steep steps: no problem for P and A – our sons, (25 and 21) – or our daughter, F (17), and not much for L. After too many years carrying too much weight and smoking too many roll-ups, it was more daunting for me, but entirely manageable, albeit with some breathlessness at the end.

Except that the breathlessness didn’t wait until the end. Less than halfway up, I was gasping for air and had to stop. I was embarrassed by my lack of condition – I planned to clean up my act in 2019 – but a recent bug had left me with some bronchial soreness, so I put my frailty down to that. I chose to be unconcerned.

After resting for a few minutes, I was able to finish the climb and enjoy the view with the New Year crowd. Getting home afterwards was entirely downhill.

On New Year’s Day, we strolled along the west bank of the Tiber in glorious, warm sunshine and the incident on the steps was entirely forgotten. We visited the Roman Ghetto, ate slices of pizza in the Jewish Quarter and looked across the city from the absurd monument to Victor Emmanuel II. It was a good start to 2019, but I went to bed with slight intimations of a cold.

The next morning the ‘cold’ was still there, but undeveloped, little more than an off-taste in the mouth. Nothing to stop me going to the Vatican as planned.

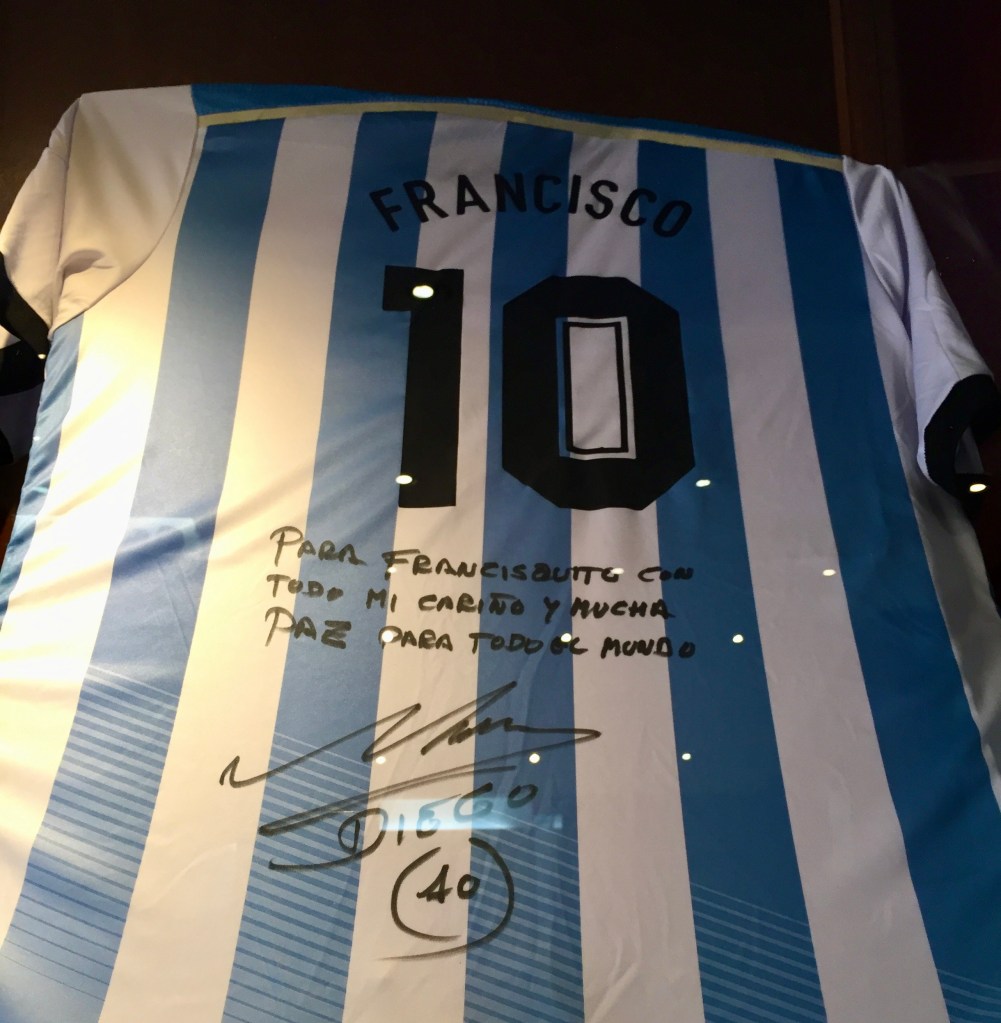

Each photo I took that day is not simply an image but a souvenir of my declining physical state. There’s one of an Argentina football shirt in a glass case – No. 10, of course – given to Pope Francis by Diego Maradona. The time stamp is just after 2pm: at this point the ‘cold’ was coming out. Just after 3pm, I snapped the bronze peacocks in the New Wing: I was thinking flu or virus instead of cold but tried to remain interested in my surroundings. And at around 4.20 pm, there are a couple of shots of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

They are bad pictures: they prove that I was there and nothing else. Because this is when things began to go wrong. My symptoms – mainly aches and fatigue – were within normal experience but I felt ill and overwhelmed. There were too many people around me. Above me, too many colours and too many stories. I was in a sacred hall of European culture and it was giving me the screaming abdabs and I couldn’t wait to leave. But I had to stay awhile – I’ d been here before but my kids hadn’t – so I scanned the ceiling, looking for God and Adam to give me a fixed point.

When we were moved on, the Matisse Room was a huge relief. Right then, I took the simple lines of the La Vierge à l’Enfant over Michelangelo every time.

In St Peter’s, while my family wandered the aisles, I sat in the Marian chapel and listened to the choir. I closed my eyes and breathed deeply for about fifteen minutes: not prayer but total retreat. Thereafter, I gathered myself sufficiently to do as visitors to the Basilica do. Was the Pietà always behind glass? I took a good team photo of the family looking happy and well.

Outside again, the winter air brought some relief. And I hoped that food would help too. But in a trattoria that evening, I managed a little red wine and a few bites of sausage and lentils before I was overtaking by violent and over-productive coughing. I went back to the apartment, leaving the others to try to enjoy their dinner.

In bed, with a fever developing, I still thought this was just a bug. We were due home tomorrow evening. I would rest, all day if needed, then dose up on paracetamol before getting onto the plane. But F felt strongly that I should not fly. By morning – after a feverish night and waking up in sweat-soaked sheets – everyone agreed with her. L called Andrea*, our host, to extend our stay for a few more nights. She would stay with me but the kids would fly home as planned.

While the family went out to the Forum and the Colosseum, I got up to let my sheets air. Another bout of coughing and retching brought up yellow phlegm and streaks of red. Traces of last night’s wine, I told myself. The routine switches between hot and cold continued, only this time, the cold part was something I’d never previously experienced. The family returned to find me wrapped in my overcoat and scarf, huddled next to a radiator turned up to eleven, and still shivering. I welcomed the fever when it finally returned.

It felt strange for my kids to say goodbye and head to the airport without me, but by now I was grateful I wasn’t attempting to fly. Later that evening, during a paracetamol-window, I joined L at the kitchen table and managed to eat something. After a night’s sleep, I told myself, I would start to improve. It would be OK.

Instead, there was another night of hot and cold, and some new developments. While L went out for essential supplies, I coughed or threw up more phlegm and more ‘wine’, although now I conceded it was actually blood. L returned and I threw up again: mostly on the bed, mostly blood. My left knee and right wrist were swollen, searingly painful, and I couldn’t push myself out of bed to get to the toilet.

L called an ambulance. Early on Friday afternoon three paramedics arrived. We stumbled through triage in a mixture of English and Italian. They looked at my puke, they looked at my knee, and then tried to move me. I was ill and in pain but still made room for shame when they struggled to get me off the bed and on to a trolley. They weren’t sure what was wrong, but their hunch was that I had a UTI.

The ambulance bounced and rattled along Trastevere’s cobbled streets until we made it to A & E at Policlinico Umberto I. A bored-looking nurse triaged me and we were directed to the waiting room. Even then, I didn’t think it was anything that serious. I was more anxious that I would soon need the toilet. How that would work? I lay propped up on my trolley, monitored up, and focused on slowing down my breathing,

But that was happening anyway.

We waited for about an hour. I had no real idea what my resting heart rate, blood pressure or blood oxygen should read. But there was a woman in the room who did. And she’d been watching my numbers. She came over to L to say someone needed to see me, now, and went with her to the front desk to help with the necessary Italian.

In a side room, soon afterwards, I watched the swirling monochrome patterns of an ultrasound of my chest, not knowing what I saw. A male nurse – whose white tunic matched his hair – asked questions in good English, while a younger nurse took blood samples. Her dark curly hair reminded me of L’s best friend. I told them I really, really needed the toilet. But they didn’t seem to hear me. Instead, more nurses appeared. They put me in a gown and after a false start, managed to cannulate me.

Unbidden, my bowels opened, and there was another moment of simple, childish shame. The curly-haired nurse cleaned me up, wordlessly, swiftly and with less fuss than if she’d been wiping a kitchen counter.

By now it was around 10 pm. I was wheeled into the corridor, where L was waiting for me. We hung around until the white-haired nurse came out and told her she should go home. They would phone if anything happened. If not, she could come and visit tomorrow. She let go of my hand and began to move away. Then, finally, I wondered if I was seriously ill, and I was frightened. A nearby nurse maybe picked up on this. He put his hand on my arm and said, in English: “Don’t worry. You’re going to be OK.”

And so I lay on a trolley in the corridor, while life in Code Red emergenza e accettazione passed by me and I drifted towards nothingness. Until the breathing. Until Chiara.

* * *

There’s probably too much detail here – and definitely too much information – but like the phone recording you never know when it might come in handy. And I wanted to look back at the red flags I chose to ignore for reasons mundane – not wanting to make a fuss, the sheer inconvenience of being ill away from home – and existential – to avert my gaze from mortality. Other commitments, self-doubt and procrastination have meant it’s taken too long to put this piece together. Reading the sepsis stories of Bethan James and Manjit Sangha recently gave me the prod I needed to carry on paying my dues.

Next time, I’ll return the strange world of ICU, with neither commentary nor analysis for a while.

* * *

*Andrea – name changed