ACROPHOBIA

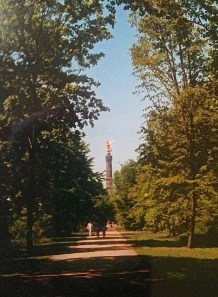

When the angels in Wings of Desire aren’t dispensing comfort, or acquiring mortal shape to take up with trapeze artists or kicking their heels off-duty in the Berlin State Library, they spend a lot of time soaring up to or swooping down from considerable heights. A favourite vantage point is on top of the Siegessäule (Victory Column). Although I have a passable ‘angel-overcoat’ there’s plenty of circumstantial evidence to suggest I’m not of their number, such as lack of pig-tail, no wings and less-than-beautiful soul. But let’s put that to one side. Conclusive proof that I’m not an angel, should it be needed, can be found in the details of a trip to the Siegessäule over Christmas in 2002.

The Siegessäule was originally designed to commemorate the Prussian army’s victories over the Danes in 1864. By the time it was completed in 1873, Austria and France had been similarly defeated and the princes of the German states had convened in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles to proclaim Wilhelm I as their Emperor. So the Siegessäule became a monument to the military and economic power of the new German Empire. The winged Victory herself – Goldelse as Berliners call her – still watches over the city from a height of about 67 metres. And a narrow viewing platform, a mere 51 metres high, gives good views of the city should you wish to climb the 285 spiral steps to get there.

The Siegessäule was originally designed to commemorate the Prussian army’s victories over the Danes in 1864. By the time it was completed in 1873, Austria and France had been similarly defeated and the princes of the German states had convened in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles to proclaim Wilhelm I as their Emperor. So the Siegessäule became a monument to the military and economic power of the new German Empire. The winged Victory herself – Goldelse as Berliners call her – still watches over the city from a height of about 67 metres. And a narrow viewing platform, a mere 51 metres high, gives good views of the city should you wish to climb the 285 spiral steps to get there.

Unfortunately, in 2002, our assembled party of two families did wish to climb the 285 spiral steps to get there. My daughter wasn’t even two back then so I carried her, as a father should, and for a while this was OK. But as we went round and round and higher and higher my fears about height took control. Worse, I started projecting them onto my little girl, who seemed way too restless and reckless in my arms. (She wasn’t – it was just me.) Eventually, her godmother took her so I could concentrate entirely on getting my jelly-legs to the top. As for the good views of Berlin, I was too busy pressing myself against the wall to notice them. I was left alone to manage a slow and grateful descent: legs trembling, mouth dry, palms sweating.

Vertigo?

It felt like vertigo. And like a lot of people I use the word freely to describe my problem with heights. It’s a proper medical condition, and it’s the title of my favourite Hitchcock film, so it has to sound better than saying: ‘heights scare the crap out of me.’ But this isn’t accurate. Dizziness and a spinning sensation are the key symptoms of vertigo, and they can be triggered by any number of situations, of which extreme height is only one. Early in Vertigo, James Stewart uses the correct term – for my problem, anyway: acrophobia. Which put simply means ‘heights scare the crap out of me.’

“I’m not afraid of heights. I’m afraid of falling.”

It’s a great line, of course, from Harry Dean Stanton in another Wenders film, Paris, Texas. But I wonder if it’s right. In my case, I think ‘drop’ is the key word. I stood in the Alps one summer and looked down on glaciers, clouds and small planes and found it exhilarating. But winding mountain paths to get there, with what to me looked like sheer drop on one side caused only anxiety. Worse, watching my kids skip quickly and fearlessly up those paths ahead of me left me panic-stricken. Cable cars are OK, provided I don’t look down when going past a pylon, which points like a giant arrow to earth and reminds me how high up I am. I’ve learned to be Zen-like about flying. But places like the Siegessäule, where you appear to be standing above well, nothing, are, I think, best avoided. And you’d never catch me up the Eiffel Tower or the Shard.

I can’t find a cause in any height-related childhood traumas. There’s a dim, small-child memory of cliff-tops, presumably from a family holiday, but it’s unthreatening. And to the best of my knowledge no-one dangled me from the top window of the house when I was a baby. So I guess it must be to do with an over-developed sense of self-preservation. Unless I’m subconsciously afraid that if I get too close to the edge gravity will whisper malevolently at my back, like an invisible Mrs Danvers of the universe, and coax me into letting myself go …

Before anyone starts calling the helplines on my behalf, I think it’s just self-preservation.

Crossing the gorge

Time was when I wouldn’t have even tried. But I did manage this in Switzerland, getting across a distinctly swingy bridge. And it was embarrassing, knowing the family were watching their useless wreck of a husband and father teetering across with rigid-neck (so as not to look down), but not without some small sense of achievement. More recently, I visited my son in Bristol and we made a return walk across the Clifton Suspension Bridge. I’d love to recount how I marvelled at the magnificent engineering and the sheer grandeur of the landscape, but of course I did neither, and kept my eyes fixed firmly on the other side.

Sadly, even though it’s well fortified with anti-climb barriers and high railings, there are large plaques with the Samaritans number at either end of the bridge. Which tells its own story, and brings me back to the angels.

It’s corny, but I find the image of crossing a gorge helpful in keeping going despite occasional depression and the paralysis that comes with it. Keep your eyes fixed on the other side, don’t stop, don’t look down and don’t look back. I’d love to think that an angel was helping us across the gorge, but I assume not, so we have to look out for each other instead.

And I hope one day to stop on the bridge above the middle of the gorge – not from fright, but simply to admire the view.